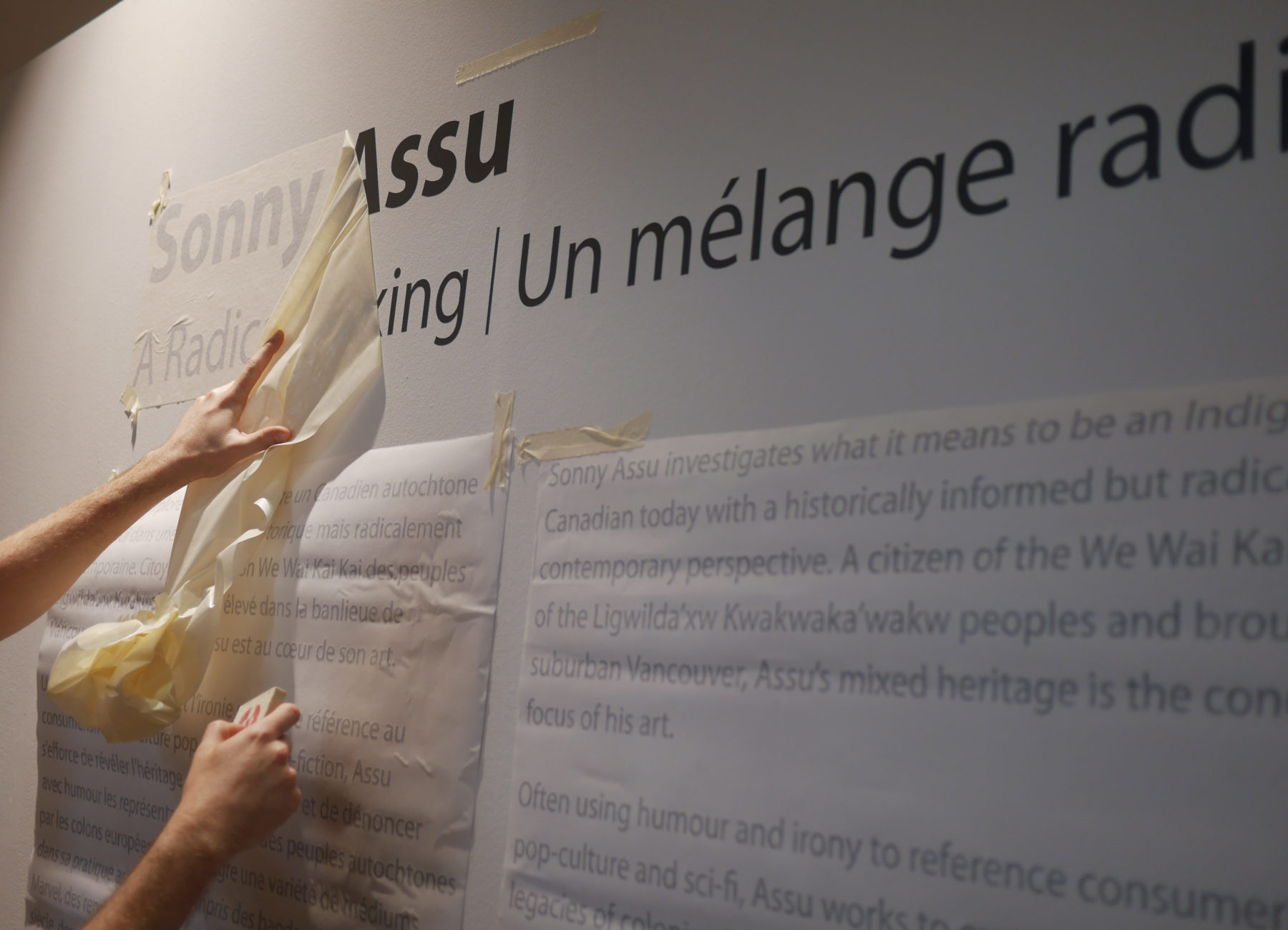

- Artist Sonny Assu

- Location Canada Gallery, Canada House, Trafalgar Square

- Artist Sonny Assu

- Location Canada Gallery, Canada House, Trafalgar Square

From sci-fi to superheroes, interdisciplinary artist Sonny Assu investigates what it means to be an Indigenous Canadian today. Raised in North Delta BC, a suburb of Vancouver, it wasn’t until Assu was eight years old that he learnt of his Ligwilda’xw/Kwakwaka’wakw roots. His work is informed by a deep understanding of his heritage, radically remixing Kwakwaka’wakw iconography with western and pop aesthetics. Assu uses humour and irony to unsettle misconceptions of Indigenous peoples and expose the enduring legacies of colonization against the First People of what is now known as North America.

Assu works within an understanding of millennia-old Kwakwaka’wakw art practices, a well-known component which is commonly referred to as the formline tradition. This complex stylistic vocabulary is comprised of ovoids, s-shapes and u-shapes, historically employed on utilitarian and ceremonial objects such as totem poles, house fronts and transformational masks. The series Interventions on the Imaginary playfully challenges the way Indigenous presence has been romanticised and/or erased, primarily by early 20th-century landscape painters. Assu tags famous paintings of the supposed Canadian ‘wilderness’ with vibrant formline elements. Reminiscent of an invading fleet of spaceships, these digital interventions propose an Indigenous futurism that speaks between generations, rewriting the narrative trope of the ‘vanishing race’ which has served to justify colonial mandates of expansion, assimilation and genocide.

Contested territories take center stage in The Paradise Syndrome, in which Assu overlays copper shields onto a collection of colonial marine charts that belonged to his grandfather. Flowing lines obfuscate and destabilise the invisible borders devised to confiscate, define and separate lands. The title references a 1968 Star Trek episode in which the crew stumble upon a planet populated by displaced Native Americans. In The Treasury Edition, Assu repurposes his childhood memorabilia, suffusing Marvel superheroes with the storytelling drive of the formline tradition. Likewise in The Speculator Boom, holding to account the publishers who emptied his piggy-bank, Assu dismantles and redistributes the inherent and conceptual wealth of his childhood comic book collection.

In Ellipsis, 136 copper replicas of vinyl records climb the gallery wall and lay silently stacked on the floor, referencing a decision made by Assu’s great-great-grandfather, Chief Billy Assu, to allow the recording of Kwakwaka’wakw ceremonial music in an era when it was illegal to perform these songs publicly. On the Northwest Coast, copper continues to be revered for its materiality and cultural significance; the installation could be wryly understood as indigenous certification, like platinum or gold albums in the dominant record industry. The copper LPs not only commemorate Assu’s ancestor but mark the number of years, as of 2012, that First Nations peoples have lived under the ‘Indian Act’. This controversial statute, first passed in 1876, imposed restrictive definitions on ‘Indian’ status and enforced an aggressive project of cultural assimilation and land redistribution. Whilst numerous amendments have since been made, the Act is still an active bill of law in Canada today.

Assu’s dual heritage allows for a liminal and creative perspective on seemingly disparate realities, as he ironizes the stereotypes and propaganda-histories that forbid a nuanced understanding of identity.

Grappling with autobiography, family history, Indigenous visual culture and the crosscurrents that shape his worldview, he proposes a radical mixing that is at once politically charged and astutely personal.